Starting in 1880, thousands of immigrants from Japan came to Oregon in hopes of finding work and a better life. Many came through Portland, and it wasn’t long before a Nihonmachi, or “Japantown,” formed in the city’s Old Town neighborhood. A growing number of young Japanese men, and eventually their wives and families, populated the area between Northwest Second and Sixth avenues. This new community created demand for hotels, restaurants, bathhouses, barbershops and other businesses owned and operated by fellow Japanese immigrants.

One of those businesses was Ota Tofu. Founded around 1911, Ota produced the familiar ivory blocks of tofu from open vats of soymilk cooked over gas-fired brick ovens.

More than a century later, Ota Tofu is one of the last — if not the only — Portland businesses to survive the period of Japanese internment, lasting from 1942–’46. Its small, shabby building stands almost forgotten between technicolor bars, large production spaces and ever-expanding condos in inner Southeast Portland. The tofu recipe has changed little from the original incarnation, and each block is still cut and packaged by hand.

Every block of Ota tofu is made by hand. Though relatively quick (Eileen estimates it takes about an hour from start to finish), the process is still labor-intensive.

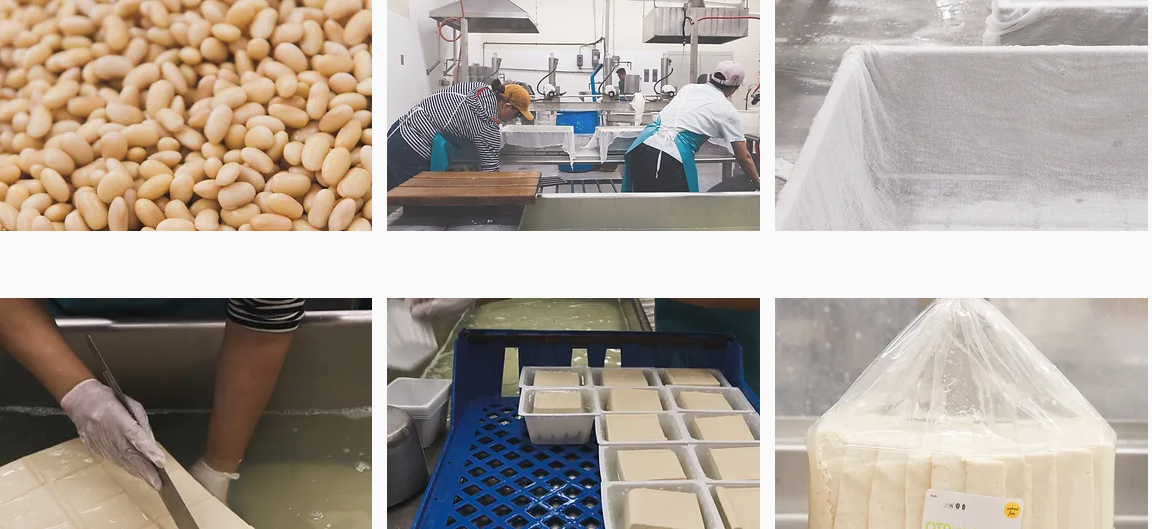

Production starts the night before, when great plastic buckets — big enough to bathe a large child in — are filled with mustard yellow soybeans and water and left to soak overnight. By 4:30 the next morning, the beans are rinsed and ground with water in a small hopper to produce a milky slurry. That slurry is then pressure-cooked and strained through mesh, leaving thick, raw soymilk behind.

Similar to cheese, tofu is made from pressed curds. Traditionally, nigari (the dried liquid rich in magnesium chloride leftover once salt is removed from seawater) was used as a coagulant. Today, Ota Tofu uses a magnesium chloride powder sourced from Japan.

Once the coagulant is added, the fresh soymilk is left to rest as the curds separate from the whey. The curds are then ladled into large stainless steel trays lined with cheesecloth where they’ll be pressed until they reach the desired firmness.

Each finished tray of tofu is then dropped into an icy cooling tank, where the entire slab is hand-cut into 24 individual blocks and chilled before packaging.

On any given week, Ota Tofu processes roughly three tons of soybeans. Those beans turn out silky, soft tofu, with a texture like perfect panna cotta. There are also medium and firm versions; a thin-pressed tofu, slowly deep-fried in rice bran oil until golden (abura-age); and a creamy, pasteurized soymilk available by the quart or half-gallon.

Tofu only became popular for many Americans within the last few decades, but the ingredient has been part of the bedrock of East Asian culinary traditions for millennia. For early Japanese settlers, tofu was a taste of home in an unforgiving, foreign country. Today, Ota’s hands-on production pays homage to an art lost to time and automation — though its future remains in limbo.

According to travelportland.com. Source of photos: internet