It is believed that the Laird's began producing Applejack for personal consumption as far back as 1698, when William Laird immigrated to New Jersey from his native Scotland. The family provided Applejack to troops during the Revolutionary War, and even counted George Washington among its fans. Today, the distillery has been in the Laird family for eight generations. Laird & Company (Source:usa today)

Considering the names that dominate the roster of extant long-running outfits — George Dickel, Jack Daniel’s and so on — it would appear that the history of American distilling is the history of American whiskey. And to a great extent that’s true, partly as a circumstance of the ingredients at hand. As Chuck Cowdery, whiskey blogger and author of Bourbon, Straight: The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey, puts it, “Anywhere you had corn farmers and good water, you had whiskey makers.”

The production of Laird & Company’s signature product begins with apples. After pressing, the resulting apple juice is fermented, distilled, barrel aged for at least three years, and finally blended and bottled. The distillery also produces 7 ½ and 12-year apple brandies. Laird & Company (Source: US A today)

But early American distilling wasn’t a monoculture. Rum was popular along the Eastern seaboard during colonial times, thanks to ready access to the cheap molasses that was a byproduct of the British sugar trade. Historically, our neighbors also shaped our spirits preferences; says Cowdery, “States adjacent to Mexico always drank a little tequila and other agave spirits.” And as immigration to the U.S. ramped up throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, bringing with it a plurality of culinary traditions, our forebears no doubt influenced one another’s tastes. Indeed, Lance Winters, master distiller at California’s St. George Spirits, imagines a bygone distilling culture as diverse as that of our immigrant past, with “different types of schnapps being enjoyed by German immigrants, slivovitz by Eastern Europeans, marc by French,” and so on.

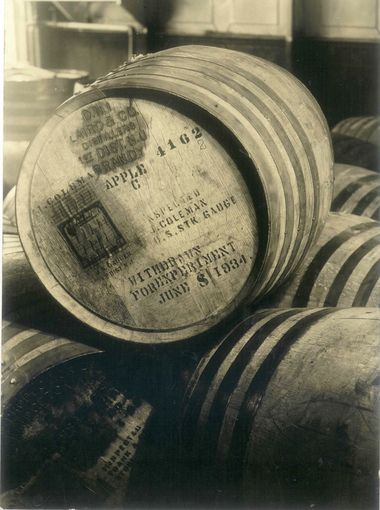

Shown here are barrels of Applejack produced after the repeal of Prohibition. During Prohibition, the Lairds kept the family business afloat by making non-alcoholic apple products like cider. Laird & Company (Source: USA Today)

The death knell for this distilling diversity? Prohibition, the 13-year stretch (1920-33) during which just a handful of distilleries were permitted to continue operations in order to produce “medicinal” spirits. Post-repeal, it took time for the formerly-vibrant spirits culture to find an audience.

The evolution of Laird & Company’s packaging provides a visual record of the distillery’s long history. While distillery tours are not currently offered, the Laird family is currently working on plans to convert a disused barn into a visitors center. Laird & Company (Source:USA Today)

Winters ascribes the homogenization of American distilling in the decades following Prohibition partly to profit motive: “Prohibition effectively wiped out a generation’s contribution to the drinking tradition, and when commercial production started back up, all the producers raced to see who could gain the most market share by making products they thought would appeal to the masses.” (Though the presence of numerous bourbon outfits among the country’s oldest distilleries would seem to suggest that our national spirit was immune to these shifts, according to Cowdery, the American whiskey industry in fact entered a period of decline that wouldn’t ease until the 1990s.) Further discouraging the reestablishment of a diverse homegrown spirits scene was a raft of burdensome legal requirements (such as the mandatory provision of an office for a federal government agent as well as a steep levy per proof gallon produced) that made it all but impossible for small distillers to set up shop.

Today, the bar is known for its fine Southern dining, list of wines, scotches and whiskeys, and menu of handcrafted cocktails. Andrew Celbulka (Source: USA Today)

Changes to this prohibitive legislation in the early 1980s finally opened the door for a new generation of independent distillers who would foster a renewed enthusiasm for a broad range of homegrown spirits. And so it is that a “new old” distillery like St. George, founded in 1982, joins outfits like Laird & Company, whose roots pre-date the American Revolution, in an accounting of the country’s most venerable spirits producers.

After founder Edward McCrady expanded the tavern and its popularity in 1788, the new Long Room hosted a 30-course dinner for President George Washington three years later. Andrew Celbulka (Source: USA Today)

SA Records Organization_USKINGS are still collecting more information from many sources and it is our pleasure listening to everybody's comments to have a full evaluation of the USA Around You: ‘Discover America's oldest distilleries in the US

According to USAToday

USA RECORDS ORGANIZATION_USKINGS

.jpg)